Girls’ House in Cambodia is a key to studying – and dreaming

Johanna Vuoksenmaa directed a video for Tommi Kalenius’s version of the Suvivirsi (Summer hymn) for this year’s FCA Suvivirsi campaign. The campaign raises funds every year for the education of children and young people in developing countries, this year specifically for education projects in Cambodia. You can check out the music video at the campaign website. The video tells the story of Yisa, a 14-year-old girl from Kralanh village, Cambodia. Many of Yisa’s classmates live in the Girls’ House.

A ninety-minute drive from the city of Siem Reap, in Kralanh village, stands an orange two storey house – spacious, open and minimally furnished.

During school weeks, it is the home of some twenty secondary and upper secondary school girls. They are part of a group of one hundred students in the Kralanh area, whose education is sponsored by the FCA (a member of ACT Alliance).

These girls come from poor families or difficult conditions, many of them are orphans or abandoned. They are provided with school supplies, school uniforms, school lunch and health care. The teachers’ fees for extra lessons are also covered.

To make the way to school easier, the girls have also been given bicycles. In the rural areas, secondary schools are often far away and travelling on the roads is difficult, especially during the monsoon season when the roads turn into soggy sludge. In order to stay in school, some of the girls have to live away from home during the school weeks.

Breaking the rules means extra housework

Whispers, giggling, shy smiles. Then, relaxed chatting and open laughter.

The visitors have clearly been expected. The teenage girls standing calmly in line seem to share a great sense of solidarity.

But, because girls will be girls, collectively drawn and common rules are necessary.

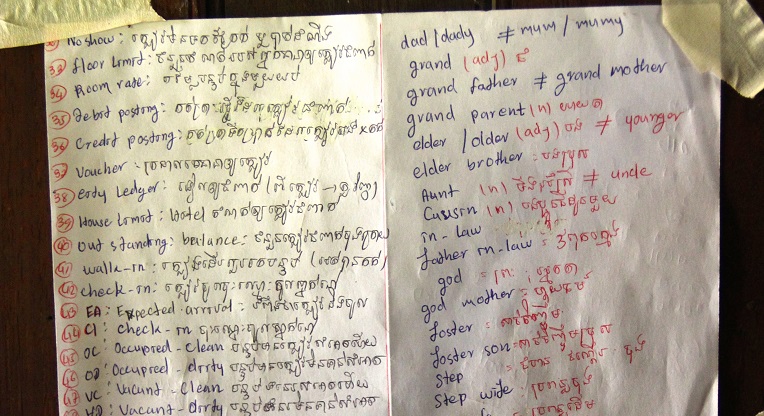

The rules are placed visibly on the wall and the twelve items listed on them include rules about curfews, cleaning duties and respecting each other’s personal space and belongings. And, naturally, about the use of cell phones (must not talk on the phone for too long) and boys (not allowed in the house).

Hub Lyhoum, 16, whom the girls have chosen as their group leader, says the common rules were easy to draw up. Extra housework is in store for anyone who breaks the rules, so slips happen very rarely.

A doctor, a police officer – or a teacher

Lan Davin (left), 18, teaches English on the weekends to the children in her home town. Davin dreams of becoming a doctor or a teacher. For 16-year-old Prin Kaya (right), physics and chemistry are the favourite school subjects.

Lyhoun, who is in eleventh grade, excels in mathematics and wants to become either a police officer or a doctor. Her friends have told her, that in order to get one of her dream jobs, she must also study English, biology, chemistry and politics.

Lan Davin, 18, who will finish school this year, misses her family, but likes living in the house, because it allows her to focus on her studies. Davin travels back home on Saturday after the school week is over, and teaches English to the children in her home town. She dreams of becoming either a teacher or a doctor.

Upstairs in the girls’ own space they do their homework and spend free time. At night, a sleeping mat is laid down on the floor. Clothes all rest amicably on the same rack in a room that probably used to serve an entirely different purpose.

Parents need support and attitude education

Despite support, some of the girls are forced to quit school. Last year, eighteen of the hundred girls who received a scholarship quit school.

Local culture has traditionally tied Khmer women to home, which is why it is essentially important, in supporting the education of girls, to influence the attitudes of the parents and the surroundings.

There is no compulsory education in Cambodia, so most girls have no choice but to bend to the wishes of their family which often, short-sightedly, prefer working and marriage over education.

In changing attitudes, it is important to support the livelihood opportunities of poor parents and the communities in a comprehensive way. When parents get support for their own livelihoods, it gives their daughters more freedom and space to manoeuvre.

Raising poultry supports training

There is a loud cackle coming from the yard of 59-year-old Leoung Pich. Even though she can’t read or write, raising poultry is a breeze.

She was widowed ten years ago and her eldest children have already set up families of their own. Only the youngest daughter still lives at home and goes to the final grade in school. When she graduates, she will become the first of Pich’s children to finish her education.

Membership in a savings group has not only helped Pich with raising poultry but also supported her daughter’s education. When the livelihood of the family is guaranteed, the daughter is free to focus on school, which is also important for Pich.

Pich’s younger sister, Bun Mach, 49, lives next door and, like her sister, raises poultry and is a member of the village savings group. Mach is also the mother of Davin, whom we met earlier at the Girls’ House, the girl who spends her weekends teaching English to the children in her home town.

Conversation is lively and the smiles on the faces of the two sisters show without a doubt how proud they are of their daughters.

Text and photos: Ursula Aaltonen

Finn Church Aid has supported the secondary and upper secondary education of poor girls and girls in danger of being marginalised in the Kralahn region in north eastern Cambodia since 2013.