US TerMINATES ALL FUNDS:

School must continue

USTerMINATESALLFUNDS:Schoolmustcontinue

About usFinn Church Aid

We believe in everyone’s right to peace, quality education and sustainable livelihoods, and we work with the most vulnerable people, regardless of their religious beliefs, ethnic background or political convictions. Our vision is a world of just and resilient societies.

Thematic areas

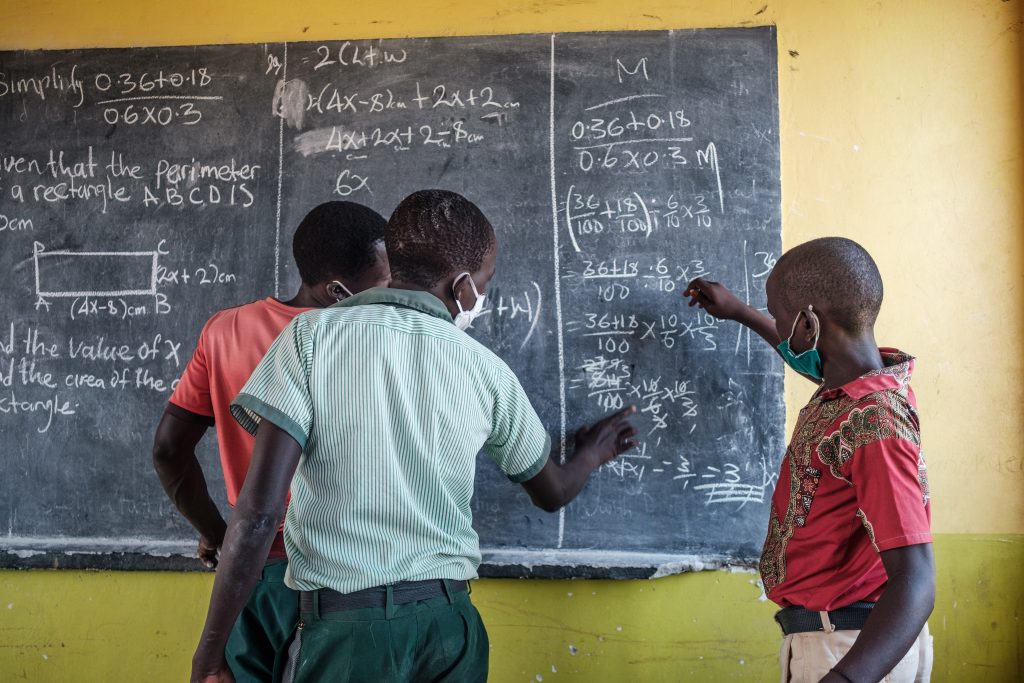

Right to Quality Education

Education is a key to stability, realising human rights and unlocking the potential of children and youth.

Right to Livelihood

Everyone has the right to provide for themselves and their families, increase their well-being, and participate in developing their societies.

Right to Peace

Peace is a prerequisite to just and resilient societies and women, youth, refugees and religious and traditional actors are at the heart of our peace work.

Annual Report 2024

In 2024, our work reached more than 840,000 of the most vulnerable people in the world.