Strengthening local governance in Somalia

Text and photos: Mohamed Eisse, FCA Somalia

Communities across Somalia’s Banadir, Galmudug, and Hirshabelle regions are reshaping local governance through participation, accountability, and inclusion. Through structured dialogue between citizens and authorities, governance is increasingly driven by shared priorities rather than top-down decisions.

LOCAL GOVERNANCE is the most visible form of government to people. Establishing community-owned, functional local governments that deliver services supports governmental legitimacy and fosters trust between officials and communities.

Somalia’s civil war collapsed governance systems and structures. The country has been steadily rebuilding since the 1990s, despite challenges like widespread drought and terrorist attacks. In the 2000s, Somalia adopted a three-tiered governmental structure: the Federal Government, Federal Member States, and local governments.

Rebuilding trust is difficult when people expect changes in their everyday lives and positive outlooks for their country’s future. Strong, inclusive local government can bridge the gap between short-term gains from trustworthy local services and the longer-term work of state-building.

Finn Church Aid has supported local governance projects in Somalia for over a decade, including the ‘Horumar’ project—meaning ‘development’ or ‘progress’ in Somali—which aims to enhance inclusive local governance and democratic participation.

Building accountability in Banadir

In Mogadishu’s Banadir region, Fardawsa Matan, a Monitoring and Evaluation focal person at the Banadir Regional Administration, has witnessed a quiet but powerful shift in how local authorities approach accountability.

Before training supported by the Horumar Project, data collection often felt routine—reports were produced but rarely used to guide decisions. Today, that has changed.

“Now we look at information differently,” Fardawsa said. “We analyse what the numbers mean for people’s lives—which services are reaching them, which aren’t, and why. It’s helped us make discussions with communities more honest and focused.”

She describes growing confidence among her colleagues to use evidence when engaging with citizens and district departments. Meetings that once revolved around opinions now centre on data and shared analysis.

“People listen when you show them facts,” she explained. “It builds trust—between departments, and between the administration and the people we serve.”

This reflects a broader shift across the Banadir region. Local officials are beginning to see monitoring and accountability not as a reporting obligation, but as a tool for improving governance and strengthening citizen trust.

“We’re starting to use evidence to solve problems instead of just describing them,” Fardawsa added. “That’s how real accountability begins.”

Bringing people together in Galmudug

The project started with consultations, forums, and capacity-building activities that brought together local officials, civil society, and community members who rarely interact in formal decision-making spaces.

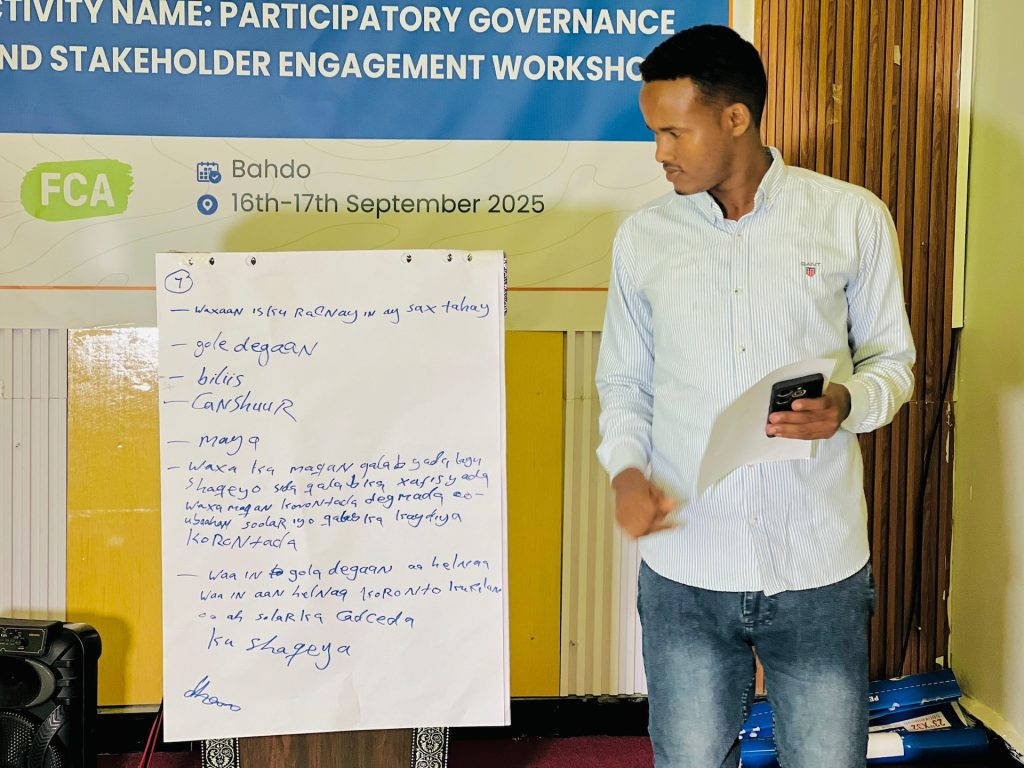

In Galmudug State, district-level consultations focused on decentralisation and participatory governance. These meetings were held in South Galkayo, Wisil, Bahdo, Abudwak, and Dhusamareeb and included district officials, state ministry representatives, civil society organisations, private sector actors, elders, women, youth, and other community representatives.

South Galkayo demonstrated how participatory planning can function where elected councils and active civil society already exist. Women councillors and youth leaders contributed to identifying governance gaps and proposing solutions, drawing on prior leadership and advocacy training.

In Bahdo and Abudwak, district administrations worked alongside elders and civil society groups to agree on local priorities, including basic service delivery, reconciliation, and community safety. Recommendations included early warning systems for conflict prevention and stronger links between communities and local policing efforts.

“For the first time, we feel our voices are being heard and our participation in governance conversations is seen as essential, not optional,” said Xidig Mohamud, a training participant.

These consultations also improved coordination between state ministries and district councils, preparing districts to manage devolved services such as health and education more effectively.

Muhiyadin Adan Wali, Abudwak district mayor, noted: “These consultations have changed how we plan and make decisions. We are not working in isolation anymore—citizens, ministries, and district councils are now part of one conversation about governance.”

Revenue transparency in Hirshabelle

In Hirshabelle State, forums on revenue transparency and civic engagement were held in Jowhar and Bal’ad. More than 200 participants took part, including women, youth, elders, religious leaders, business owners, persons with disabilities, and local officials.

Community members raised concerns about paying taxes without seeing improvements in services. District authorities responded by explaining how revenue is collected and allocated, and by committing to clearer communication around budgets and spending.

Several practical measures were agreed during the dialogues. District offices introduced suggestion boxes for anonymous feedback and complaints. Community oversight committees were formed to monitor revenue collection and expenditure.

In Bal’ad, locally collected revenue has already been used for visible public investments, including constructing a government guest house and purchasing a firefighting vehicle. These actions demonstrate how local taxes can be linked to tangible services.

“This transparency helps reduce conflict and builds trust,” said Fartun, a youth representative from Jowhar. “When people see where their money goes, they are more willing to take part in governance.”

Community safety in Bal’ad

In Bal’ad, governance discussions extended to community safety through a Civil–Security Protection Forum. The forum brought together local authorities, police, national intelligence representatives, judicial officials, women, youth, minority groups, and persons with disabilities.

Participants discussed security challenges, civilian protection, and the relationship between communities and security providers. One outcome was an agreement to establish a Community Policing Unit, bringing together security agencies and community representatives to improve communication, encourage joint patrols, and support early conflict prevention.

The forum also proposed using public events, youth sports activities, and community meetings to promote safety awareness and prevent violence.

Looking forward to prioritising communities

Even within a few months, several changes in governance practice became evident across the target regions. Local leaders became more willing to share financial and security-related information with communities. Women and youth played active roles in discussions on transparency and fair resource allocation, reinforcing more inclusive decision-making.

In the coming months, planned activities include further training for district councils, continued support for Galmudug’s decentralisation process, and the establishment of civil society oversight committees in Jowhar and Warsheikh. Community feedback mechanisms will also be expanded to improve communication between citizens and local authorities.

Through ongoing dialogue, capacity building, and transparency measures, districts in Somalia are continuing to test and refine approaches to local governance that respond more directly to community priorities.

—

The Horumar project—formally known as the “Strengthening Inclusive Local Governance for Democratic Somalia (Horumar) Project”—is a Somali-focused initiative that involves Finn Church Aid (FCA) as an implementing partner, with support aligned with the Somalia Stability Fund (SSF) III strategy.