Amid uncertainty, IDPs in Syria dream of becoming engineers, teachers or car dealers

Syria has 6.7 million internally displaced people (IDPs), many of them children displaced by conflicts, violence and natural disasters. We work with the EU’s European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) to make sure that schools can be an anchor in children’s lives, even in the midst of crises.

“We’ve had to move many times. I hate the feeling of living in chaos and uncertainty,” says Syrian Rida Issa.

Syria is home to a generation of children who have lived all or at least a big part of their lives as refugees or displaced in their home country. Rida belongs to that generation. During the armed conflict, his family kept rebuilding their home in East Ghouta, over and over again.

When the fighting ceased, the family returned to their old neighbourhood. But their home was in ruins, and now Rida lives with his grandparents.

Some 6.6 million Syrians who fled the war live as refugees in neighbouring countries like Jordan or Turkey, and some even further away on the Greek islands or central Europe. An equal amount – 6.7 million in a country of 17.5 million people – continue, like Rida’s family, to live in internal displacement within Syria.

For the time being, the fighting in Syria has abated. Nevertheless, in 2020 the country reported having more than 1.8 million new internally displaced persons, almost all of them fleeing conflict and violence.

- At the end of 2020, there were a record 55 million internally displaced people in the world. More than 26 million people have fled their home country and been given UN refugee status (2019).

- In 2020, 40.5 million people had to flee within their home countries. This is the highest annual figure in a decade.

- About 85 per cent of internally displaced people have fled their homes due to conflict or violence. The rest have fled natural disasters, most of which were weather-related (floods, heavy rains, cyclones).

- The report authors say that it is particularly worrying that these figures were recorded despite the Covid-19 pandemic, when movement restrictions obstructed data collection and fear of infection discouraged people from seeking emergency shelter.

Sources: Global Report on Internal Replacement 2021 by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and a Relief Web news article on the report. UNHCR.

Internally displaced children face many risks. Their chances of attending school and receiving healthcare and protection are compromised. Not only are children torn away from their familiar environment and communities, but they may also be separated from their families and put at an increased risk of child labour and child marriage.

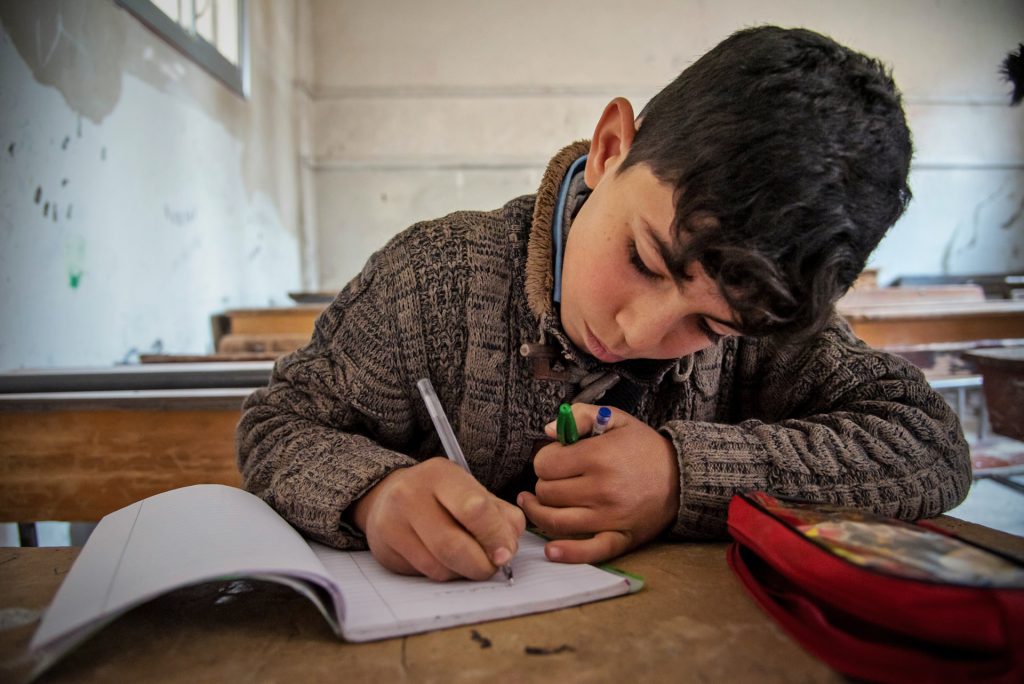

Living a conflict-torn life as a displaced person affects each child in different ways. Below, Syrian children in Finn Church Aid-supported schools tell in their own words how they feel about it.

Remal & Enas: Saddened by memories of guns and an absent father

Year 4 pupil Remal Tahina goes to school in the Daraa area. Remal finds learning difficult but hopes to follow in his father’s footsteps as a car dealer.

“During the war, we had to leave our home village for somewhere else. I still remember the grenades, missiles, tanks and rifles. There were always guns nearby.

Once a mortar shell dropped close to our home. My grandfather could’ve been injured, but luckily he was in the mosque.

My family includes my father, mother and two sisters. My father is working in the United Arab Emirates because he couldn’t find work in Syria. My uncle offered him a job at the car dealership and he accepted so he could support us. I miss him all the time. He only visits us during the summer and brings presents. Once I got a bike.

At school, I have difficulty reading and writing. My friends start fights with me and then say they’re only joking. That bothers me.”

- Our work in Syria focuses on rebuilding the war-torn education sector.

- This includes repairing school buildings, providing necessary supplies and offering remedial classes for students who have been or are at risk of dropping out of school.

- In 2020, a total of 9,345 students were able to continue their learning in refurbished school buildings. A total of 4,749 learners participated in our learning support activities. 3,000 students received a school uniform and school supplies. We offered training to 108 teachers on psychosocial support and teaching in disaster conditions.

Enas Alasimy, 12, also talks about how the war has affected her. During the war, the Alasimy family spent seven years as refugees in Jordan.

“I don’t remember much about the war because I was really young. I’ve heard people talk about gunfire, shootings and firearms.

I’m having trouble at school. I’m too scared to raise my hand and participate because I’m afraid the teacher will hit me if my answer is wrong.

When I grow up, I’d like to become a teacher to help shy students like me not to be afraid.”

Muhammad: Long days at the construction site

Muhammad Abdo Hijzai, 13, from East Ghouta goes to Finn Church Aid-supported remedial classes in maths and other subjects. With nine family members, money is tight in the Hijzai family and Muhammad has to go to work.

“When school ends at one in the afternoon, I go to help my father. He is a construction worker; we plaster walls together and prep them for painting. My dad can’t do all the work alone, so that’s why I help him.

After about six hours of hard work, we stop when the sun goes down. When I get home, I open my school books. I do it to achieve my dreams and make them come true. I can’t spare much time for homework, but I do my best: I study one to three hours a day.

On weekends I play with my friends because we don’t work on Fridays. I wish I could be with them more often, but I can’t leave my father to cope with all the work on his own. All of my older siblings are girls, so they can’t get involved in this type of work.”

Aya: Half a life in war

Aya Darwish, 14, who lives in East Ghouta, noticed how difficult it was to resume studies after years of war.

“I’ve always drawn. I draw when I’m sad. I draw when I’m angry. Ironically, I think my drawings are at their best when I’m at my worst.

I have clear memories of this long war we have had to go through. Things were really hard, and I don’t even have to go into details. By the age of 14, I have spent seven years in war. For half of my life, I have seen the worst things happen in life. That’s why I am grateful for every good thing that happens to me.

In those seven years, I almost forgot what it was like to go to school. After that time, it was difficult to start studying English again because I hadn’t used or heard the language for a long time. Remedial classes have helped me a great deal.

I don’t think painting will ever be more than a hobby, but I still dream of opening my own art galleries. That would give me an opportunity to exhibit my paintings and share my view of the world.”

Dreams stay alive, despite difficult conditions

For children living in conflict areas and as displaced, schools are crucial because they help build a sustainable future and give children the skills to earn a living.

When he was small, Omar Al Zuhaili, 14, had to flee his home village. But he has been able to return and now attends a refurbished local school.

“I want to become an architect because I like drawing and designing buildings. I want to achieve my dream, whatever the circumstances. I encourage my friends to complete their studies,” says Omar.

Education is also a powerful tool to eradicate child labour. Rida Issa, who is 14, knows he’s lucky because he doesn’t have to go to the construction site to help his father. Rida stresses that there is nothing embarrassing about working, but says he hopes that his classmates who have to work will be able to complete their schoolwork.

“I want to become an electrical engineer because I love inventions. I once designed a small spider from scrap metal. It had a small engine which made the spider vibrate and move,” says Rida.

Text: Ulriikka Myöhänen, Middle East Communications Specialist

Sources: Global report on Internal Displacement. Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (2021). Lost at Home. UNICEF (2020).