Breaking down language barriers at school

Abraham Bashombana Aganze, a Congolese young man, interprets school lessons for refugees. In his opinion, the key to a good life is dedicating it to helping others.

THE BRUTAL CONFLICT in the Democratic Republic of Congo, continuing for over three decades, has created over five million refugees. About half a million of them have crossed the border to neighboring Uganda for a more peaceful life. Abraham Bashombana Aganze, 30, from North Kivu, is one of them. He lives in Nakivale refugee settlement area, established in 1958.

Abraham, who has a university degree, had to escape violence in his homeland in 2020. For him, it was easier to settle in the Uganda than for tens of thousands of other Congolese people. In the university, his major was English – one of Uganda’s official languages. Most Congolese have never studied English, as education in DRC takes place mostly in Swahili and French.

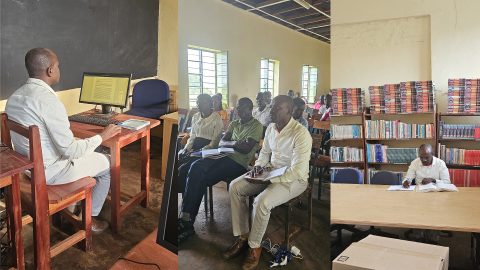

This language barrier is one of the most urgent threats to the continuation of education for those coming to Uganda as refugees, particularly from the DRC. Abraham noticed the problem soon after settling in Nakivale refugee settlement area and wanted to help. Now, he works as a volunteer English interpreter in Rubondo community, in a school supported by Finn Church Aid.

”I started volunteering after some youth who know me came to request me to teach them enough English to go to school. I soon figured out this would be the best way for me to help the most people”, Abraham says.

”My philosophy? Life is about helping others.”

Becoming a refugee turns your whole life upside down

As an interpreter, Abraham participates in classes and helps the students whose English is not good enough follow the classes. The school has both local students and refugees, like many other schools in Uganda. The regular staff of the school consists of Ugandan teachers who, in turn, don’t speak Swahili or French. For this reason, youth with a refugee background struggle to understand the lessons.

Abraham gets a small monetary remuneration for his volunteer work. He usually spends five days a week at the school.

”If, for some reason, I can’t get to the school, students I know come to my house to ask for help with homework.”

Becoming a refugee turns your whole life upside down, even in a neighboring country. To Abraham, being a refugee means financial uncertainty, as they can no longer work in the areas they’re familiar with becausethere’s no job for their training. Uganda makes the lives of the refugees easier by giving families plots of land for farming. Abraham’s family has also received a plot to till.

” Here, one needs to literally be growing one’s own food. I’m a city boy and did not know a thing about farming, until hunger forced me to learn.”

Dream of an English-language learning center

Abraham has been able to also utilize his language skills by working as an interpreter for Finn Church Aid visitors in the Nakivale refugee settlement area. Being a young man, he has many plans – establishing an English-language learning center for the area, improving the productivity of land through composting, and learning more about forms of agriculture that help in building a better life. Abraham knows it will be a long time before he will be able to return home.

”When I sit down and think about my homeland, I feel a great sadness welling inside me. I want the Democratic Republic of Congo and her people to get on its feet and get stronger. Education is the key to all of this – that’s what I believe.”

According to Abraham, few Congolese youth dream about returning to their homeland. The trauma left by the war and the violence runs deep. Still, life as a refugee is not easy in Uganda, either. Thus, Abraham wants to do his part for the youth of his homeland.

”All of our knowledge and wisdom dies with us unless we share it with others. If I share what I’ve learned to hundred people, for example, they will share them on to at least hundred other.”

Text: Elisa Rimaila

Photos: Antti Yrjönen

Translation: Tatu Ahponen