How can we build peace in an unstable world?

Everybody wants to live in a peaceful and stable society. Still, many societies have internal or external tensions and conflicts. Mediating between sides in a conflict can be a long and frustrating endeavour, but when it succeeds it has the capacity to positively impact generations of lives and give a voice to marginalised groups.

Text: Björn Udd

Main Illustration: Julia Tavast

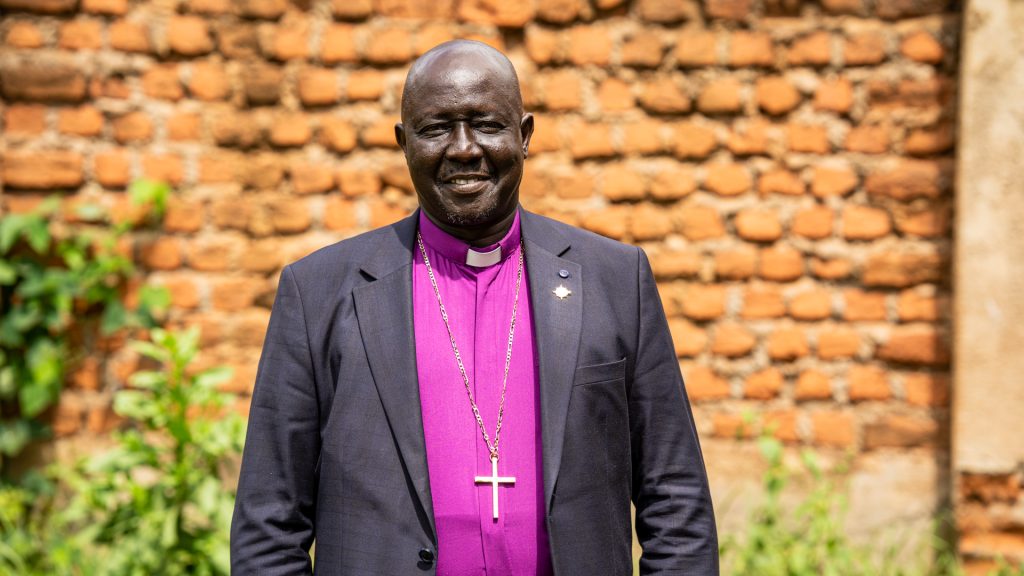

“We try to go in as soon as we heard something happened, sometimes even before the conflict has broken out,” says Most Rev. Archbishop Paul Yugusuk.

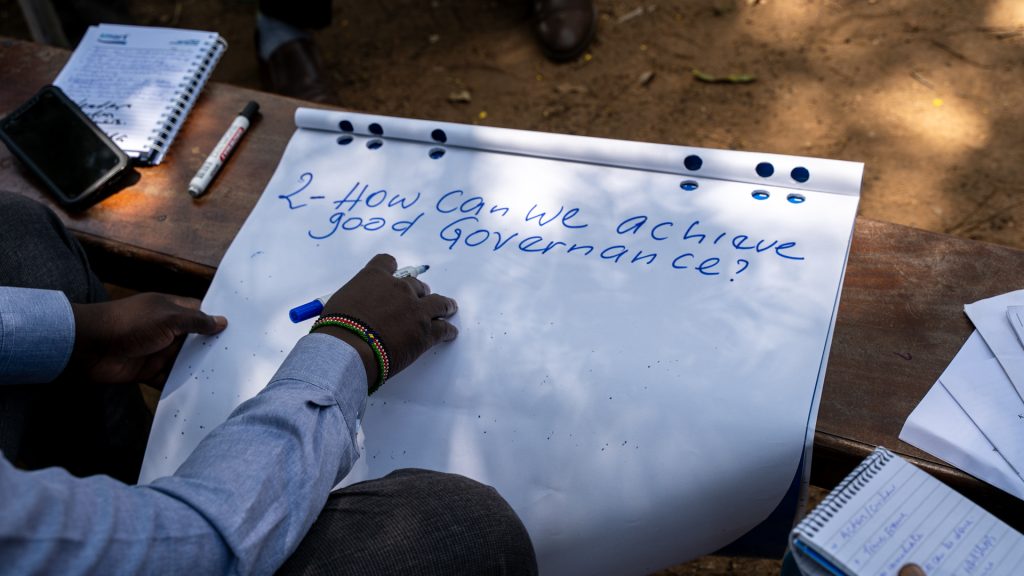

He has travelled from Juba to the South Sudanese town of Yei to facilitate a workshop on mediation and peace work, aimed at religious and traditional leaders.

Equipping the religious class with tools to solve conflict is important, since they are often the best choice for resolving conflicts between communities. They are accepted, respected and listened to, have a good understanding of the different sides of the conflict and the culture affecting it.

“When we go in to mediate, we start by finding out exactly what happened. Then we can intervene, inform the parties that retaliation is wrong and find justice.”

Archbishop Yugusuk says finding out what happened is usually not that difficult. Most conflicts in South Sudan have a known origin: rebellions, clan conflicts, and border conflicts. The issue is that they often play out in remote areas, places where the government is weak, and police is nowhere to be found. That makes mediation and peace work potentially dangerous.

“The most difficult conflicts are the ones involving arms. Even getting there is hard, because you might be shot. In the worst cases we either have to wait for the government to arrive or the most intense part of the conflict to die down. That is usually a big challenge.”

Archbishop Yugusuk has worked with FCA on peace building for over ten years.

“The most important part of the collaboration has been the consultation and support we receive. Learning how to bring the parties together for dialogue. To have separate discussions before the actual peace talks. Usually, when we bring the parties to the table the deal is already 80% done.”

What is peace work?

Not all peace work is created equal. FCA works in many different environments, and work done has to reflect the situation. While making use of religious structures works in South Sudan, different conflicts have different resolution methods.

“In Somalia we are big on reconciliation and strengthening local governance structures, while in Kenya we are looking to support formal and informal peace processes and create early warning systems,” says Aziza Maalim, Senior Thematic Advisor on Right to Peace at FCA.

In Kenya one of the main engines of conflict is cattle rustling. In those cases, the peace work must be done at a grass roots level.

In Kerio Valley in Kenya cattle, camel and goats are valuable possessions and great investments, their upkeep only requires feeding them grass. By selling some cattle, families can pay for significant expenses, like school fees. This also makes cattle a prime target for theft. Usually men in one community work together to raid another community and steal cattle. Often the conflicts become violent and lead to injury and death.

“Some thieves killed my father in 2002. I was a small child back then,” says Festus Kipkorir, from Kerio Valley.”

He was able to go to school up until eight grade. Then he dropped out. He held a lot of anger and first had a weapon in his hands when he was just 13 years old. But he knew his mother wouldn’t approve of him participating in cattle rustling.

”My involvement in cattle rustling was revealed to my mother when she hadn’t seen me for a while. I tried to explain to her that it was about me, not her,” says Kipkorir.

Education, or the lack thereof, is usually a factor in cattle rustling. The raiding parties usually consist of uneducated young men. This was also the case in Kipkoiri’s case – without the possibility of another path in life he was easily recruited by the cattle rustling gangs.

With the support of FCA he was able to return to school and left the cattle rustling lifestyle for farming.

”At first, I didn’t believe him when he said he was leaving cattle rustling and starting to farm. But eventually, I began to believe. I helped Kipkorir buy seeds so that he could grow green lentils and beans,” says Salome Kiptoon, Kipkorir’s mother.

Without including marginalized groups there cannot be lasting peace

But it is not only local conflict that requires a grassroots level intervention. For peace to prevail, everybody must be included and have a say. If people feel left out, it is very likely that the conflict will flare up again.

“We aim at creating positive peace, which demands inclusivity. We need to ensure that women, youth and marginalised communities are actively participating in the peace processes. There are so many obstacles, and they need to be overcome,” says Maalim.

In many cultures it is the women’s job to tend to the children, cook food, and fetch water. When one is burdened by all those responsibilities, they are not able to find the time to participate in lengthy peace talks.

“This is very unfair. Women usually play a big role in liberation and emancipation movements. We’ve seen that in Africa, in the Middle East and in other places. But after, for example, independence has been achieved, the women are side-lined. They are affected by all these political issues and decisions but are not allowed to participate.”

This is the reason FCA always aims to include disenfranchised people in peace talks. For example, in Somalia, FCA and its partners have promoted inclusive local governance for the last decade.

There we – together with partners like the Network for Religious and Traditional Peacemakers, Somali Peace Line, Somali Stability Fund and the Ministry of Women – have trained more than 700 women in leadership, lobbied for women’s meaningful participation in federal and district elections, and advocated for a 30% quota for women.

These efforts have paid off. In 2023 three women were elected as District Councillors in Jowhar district in Somalia, out of a total of 26 councillors.

“Women’s participation in politics and district council formation is essential for building a more inclusive and democratic society. As one of the elected women on the new district council, I am confident that we will work hard to represent the interests of all women in Jowhar”, said Faadumo Farah Jima’le, when she was newly elected.

In addition to supporting women, FCA also supports youth, to strengthen local governance structures and create more inclusivity. Youth are often overlooked in political elections.

Mohamed Ali Ahmed, 25, serving as the second Deputy Mayor, conveyed his vision for the youth’s role. “As the youngest council member of the Jowhar district, I will fully represent the district’s future and its youth. I am confident that the youth representatives on the new district council will work hard to have necessary public services and represent the interests of all youth in Jowhar. “

While quotas have proven effective in securing political rights for women – and have been included in the constitution of states like South Galkayo, Afmadow and Barawe – the number of women in leadership roles is still far from the 30% quota.

When peace agreements break down

One of the more frustrating things about peace work is that it is not always a linear process. Sometimes you take one step forward, just to take two steps back.

”Sometimes, you just have to accept that the deal you’ve been working on for two years doesn’t work. Then you have to be ready to go back to the drawing board,” says Aziza Maalim.

This is especially frustrating when projects have closing dates, and the deadline is approaching.

”Peace projects have to be very flexible. The project might have to be extended, or we might have to shift focus if one area suddenly becomes peaceful, while a new conflict starts in the vicinity.”

Opportunities discourages conflict

One example of an area where things shift rapidly is Central African Republic. In a post-conflict society where under 40% of the population is literate, rumours spread quickly and can have a devastating effect. That is why FCA supports youth clubs in CAR, to create spaces where young people can share thoughts and come together.

“Many rumours are also spread because a person simply takes pleasure from them and wants to create a scene. I’d say most rumours here are born just because someone seeks attention or because they have been manipulated by people with political interests who want to destabilise things”, says Estella Banga, member of one of the youth clubs founded by FCA in Bangui, the capital of CAR.

The latest major rumour spread like wildfire just two weeks prior. There was talk of an imminent attack on Bangui. In a society where most people have experienced recent heavy conflicts, many started preparing to flee. The youth in the clubs are taught to disseminate information and to get to the initial source to see if there is any truth to the rumours.

It is important to involve youth, since they can often be incited to commit violent acts, something that happened during the civil war starting 2013.

“The youth have been actively involved in working for peace, because the youth also were at the core of the things that were going on back then. Us youth can more easily agree when speaking with each other, without getting elders involved”, says Banga

The youth groups also address the rampant unemployment experienced by the people of CAR. Bangas group has received support to start a soapmaking business. The members are allowed to borrow the income against a 5% interest rate. These loans are often used to start personal business endeavours.

The income is important. Having an income discourages bad habits, like violent behaviour or drug use. These habits have a destabilizing effect on the community, and without them peace is much more likely.

“To me, peace means that you can move freely. The key for peace is that youth have opportunities to change their lives for the better, by their own means”, says Banga.

The Network for Religious and Traditional Peacemakers

In addition to these means, FCA works with peace through The Network for Traditional and Religious Peacemakers. The Network was formed in 2013 after a call by the then Secretary General of the United Nations, Ban Ki Moon.

At the time, there was a feeling that religious and traditional peacemakers were often left out of processes in favour of politicians, but that they had much to give.

“Most of the people in the world profess a religious affinity, and a significant percentage of conflicts have some aspect of religious or identity as a base. Political solutions might not take this into account. Religion gets manipulated to fuel conflicts, and that’s when interfaith dialogue is important”, says Gina Dias, Regional Program manager for Sub-Saharan Africa at the Network for Religious and Traditional Peacemakers.

Dias notes that different communities usually live harmoniously together, but when conflict erupts those dividing lines might become front lines. When that happens clan leaders or priests can calm the situation down.

“Our partners in Kenya train Catholic priests on Islamic theology. Then, if violence erupts, the priests are able to understand the other side and speak to their constituency. Since they are leaders, they will be listened to.”

The Network, supported by five organisations, including FCA, the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the UN, currently has 130 member organisations, 42% of them in Africa.

The members of the network usually focus on preventing violence, preventing extremism, supporting marginalised groups like the disabled or LGBTQAI, or similar endeavours.

“We see ourselves as a facilitator and coordinator. We offer trainings, help identify gaps, give financial assistance and assist with research. We want our members to do evidence-based interventions”, says Dias.

The projects of the member organisations vary vastly, it can be anything from supporting national reconciliation in Somalia to supporting local communities in negotiating with extracting industries in Mozambique to assessing provisions in the constitution for religious minorities in Kenya.

“The network has really succeeded in growing. It reaches from high-level to grassroots level, and we are able to support the actors we work with and help them achieve their objectives.

What is successful peace work?

But what have the main achievements been in the peace work FCA has supported? Aziza Maalim says the most important moments are when the people involved change their mindsets and choose to open up the peace process for disenfranchised groups.

”In Kenya we had women who actually led the mediation process on a land dispute. This was unheard of, especially in that area. When the violence crossed over into the next county, the Regional Commissioner called me to ask where the brave women are, and if they can come help mediate. That was a huge shift in perception.”

And although both the region and the world seem very unstable at the moment, with new conflicts starting in different regions of the world, Maalim has plans and hopes for the future.

“We want to do more evidence-based reporting. We want to see what worked in one country, take those lessons with us and try the best practices in other countries. We want to strengthen the synergies between FCA’s peace work and our work in livelihoods and education. We want to take climate change into account even more than now, and see how we can build lasting peace, from the bottom up.”